- Home

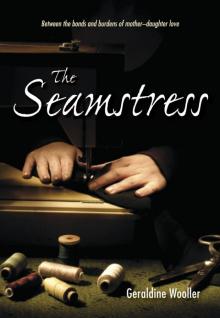

- Geraldine Wooller

The Seamstress Page 2

The Seamstress Read online

Page 2

On the whole I like the slow, watchful walk of the skinny street girls whose history is no doubt less cosy than that of these fortunate joggers.

There are two tasks to attend to. One is a daily occurrence and it concerns the living: Willa. The other is a one-off and it will be to do with death; I may see to the second one next week, or next month, or later. Run-of-the-mill matters, both, yet weighty, important duties. Thinking of them gives me both pleasure and pain.

I could defer them.

Ah, there’s Teresa, my Italian friend from around the corner, trudging along with her son’s old dog because he neglects it. Teresa wears an old skirt and a loose blouse that hides her swollen belly. No doubt a prolapse from having too many children. I wave and Teresa lumbers over so I have to slow up. We chat briefly in Italian, me dredging up enough to manage an exchange. Teresa asks as I take my leave—and I see it coming:

‘Excuse me, signora, but are you married? I see no ring…’

‘No, signora, I’m not.’ Keeping a pleasant look on my face.

‘Oh, sorry, sorry,’ says Teresa, struck with regret, extending a hand to the arm in consolation.

‘Please don’t be, Teresa, really. I’m happy not to be married. Very. Contentissima.’

But Teresa’s head is rocking from left to right.

‘Oh Dio, mi dispiace…but how do you manage?’

I leave the signora to her commiserations.

On the wall near my house someone has written Life sucks.

Underneath it another pen has put: And Naomi sucks grils. Still another scribe, a pedant, has pointed out: You mean girls. And finally in tiny letters the wag has added: What about us grils? Philosophy and wit still putting up a good show on the mean streets of Highgate.

Once back home I take off my sandshoes—damned if I’m going to call them trainers or runners, for they are not—and give the little dog her two biscuits as I think about men and women. There was Michael, and then Richard, and others whom I favoured while flying under false colours.

Willa climbed the stairs to the Trades Hall flats, on a February morning in 1935 when the air was warm and cloying. The staircase was swept clean and the interior, with its cool blue and white tiles, leading up from the dusty pavement and the front door, soothed her. Her white linen skirt and organdie blouse were simple and crisp, accompanied by court shoes, and all set off by a straw hat with a wide brim, set at a slightly rakish angle to temper the rather stiff blouse.

She almost didn’t enter because of that pavement: stained with piss and the remains of vomit, testimony to the Workers’ City pub nearby. This part of town was where girls in alleys allowed themselves to be pushed up against walls for five bob, two and six if you were no longer a girl.

Sewing was her trade: some called her a dressmaker, others a knitter. Her crochet and embroidery were works of rare beauty. But she didn’t really mind how her work was seen, as long as it was sound to her, and pleasing. She thought of herself as a tailor, and was grateful to have the tag, to have finished her apprenticeship. Her employer had kept her on, seeing that she was a conscientious girl.

Her married sisters, who used to work in the same factory, were less meticulous: Eve, fast to the point of impatience, and as a result had made mistakes. Rose and Ivy had been slapdash. But Willa was in line for Second-in-Charge of Gents’ Coats within a couple of years. A sobering thought. She had just bought herself a large, shiny black Singer machine, a handsome object she’d paid off at a shilling a week.

As her white-gloved finger reached towards the button to press the bell of the first-floor flat—not too long a ring—she heard, then saw, coming down the stair a man whom she judged to be middle-aged, about forty. It might have been the way his grey crinkly hair was combed back from the broad forehead, or the way his candid eyes took her in yet didn’t linger long enough to be disrespectful. Whatever it was, he reminded her of her brother, far away.

Ken was holding out a firm hand to shake hers, something men only did to each other, usually. She clasped it, saying in a voice with the trace of a Scots burr: ‘How do you do? I’m enquiring after the room.’

‘I’ll get my wife,’ said the caretaker.

Gina had a smile that took off from deep-blue eyes, and was rapidly taken up by the rest of a strongly featured, Italianate face. Her dark hair was swept up at the front, away from her face, and she moved in a way that, it seemed to the younger woman, conveyed grace and sympathy. She didn’t bustle, in the way of landladies.

‘It would be just perfect,’ Willa smiled but half shook her head, looking at the bedroom and tiny sitting room, knowing it was too good, too clean and convenient, to be affordable. And to live near people like these.

‘Do you have family here,’ asked Gina, inclining her head to one side. She didn’t wish to pry.

‘I have sisters here and a brother. They’re all married. My mother has gone back Home with my eldest brother.’

Ken and Gina stood on the landing with her, guessing her worries.

‘At least you’ve got a good job,’ Gina said. ‘Cup of tea, Willa? We can sort something out.’

And Ken nodded, saying, ‘Yairs, yairs.’

The girl was moved that the woman and her husband should imply that any difficulty was something the three of them would tackle. As they went up to the caretaker’s flat Gina explained that she and Ken had two little girls, one a baby; they were keen to have a good tenant in the downstairs flat.

‘I do want a woman like you here,’ and her voice was confidential. ‘It could be seen as a bit…unsavoury, this area.’ She lowered her eyes.

Willa nodded and said, ‘People out of work, not enough to keep them occupied.’

‘That’s right. But it’s not dangerous around here. Sometimes it gets noisy, though we don’t have any trouble. Not at all, really.’

‘I’m not easily frightened,’ Willa laughed. She had the face of a woman on the cover of the Ladies Home Journal of the time.

The table was simply laid, every item in its dish, an immaculate tablecloth, bread and jam, tea. Simple fare, an honest table; so like her own mother’s that Willa took a deep breath, the beginning of a sigh, fleeting regret.

Her father had died last year and her mother had gone back to the old country with the oldest son. Willa saw her parents in younger form in this couple: a comfortable partnership, pleased with each other, as if they would never outwear their thankfulness.

‘You make a lovely cuppa, Gina Verdina,’ said Ken, mock smacking his lips. He smiled at Willa as if to say that having a wife with such an outlandish name would always amuse him.

‘Oh, you say that every time, Kenny.’

A little girl came in, and sidled up to the new lady in the pretty clothes and whispered, ‘Are you going to live here with us?’

The enveloping kindness in the kitchen hung around them.

‘I think so,’ Willa said, as she put an arm around the tiny shoulder.

Ben sat in the only easy chair in the flatlet, legs apart, elbows resting on his thighs, hands folded in front of him. Not an elegant attitude. He was smartly dressed, in a suit, almost debonair, but no, you wouldn’t call him elegant. He was a butcher, after all.

‘I’m nearly finished,’ she said to the garment that was between her hands directly under the machine’s deadly stabbing needle.

She didn’t take her eyes off it, deftly turning the material around; then lining it up once more, she unhitched the clasp above the needle, moved her right hand to the warm wheel and stepped on the treadle firmly. The whirr of the machine saw to the last stitches and the task was completed, the finishing touches having been put off lovingly like a treat. Unhurried, she drew the dress away, and neatly snipped the thread with a barely audible noise, the ghost of a sigh.

He heard the satisfied sound and thought: Enough to make a man bloody jealous. He noted her long fingers, the soft skin of her cheeks, the curling hair on her neck, the short skirt at her knees. She had his full approval, h

is undivided attention. He could hardly credit he’d got her.

She stood up and held out the creation at arm’s length for his inspection, her eyebrows raised in a question.

‘Beaut,’ he said. Then, because she apparently needed more: ‘It’s beautiful.’

‘Do you like the colour?’

‘Too right. Put it on.’

‘Turn your back.’

He was incredulous. ‘After what we’ve been doing?’

She flushed. ‘Still…’

‘All right,’ he said, crossing a leg and turning his back to her.

‘Do you think they can hear us, upstairs, when you’re here?’

‘Nah. Anyway, Ken wouldn’t care. What’s it to them? Got my doubts about that nipper, though.’ He gave a chuckle. ‘Little bugger.’

On cue there was a scratch at the door.

‘That will be Lisa now,’ said Willa, zipping up. She unlatched the door and the child slipped in, all eyes, a mop of hair.

‘G’day, sweetheart,’ said Ben, sweeping her up in his arms and smacking a great kiss on her cheek.

She giggled and looked at Willa.

‘Are you going dancing?’

Willa nodded, showing dimples when she smiled, the trace of a wink at the little girl as though sharing a secret.

‘To the Trocadero,’ Ben said, prancing around the tiny space with Lisa in his arms till they both fell on the bed.

‘Do you like my dress, Lisa?’

And the child scrambled to Willa’s side, nodded vigorously.

‘When I grow up I am going to be just like you.’

They all sailed out of the room and Ben, feeling good, put the little kid on the steps of the next flight, up to Gina waiting on her landing. He gave the woman a salute with his head, that Australian gesture of a half-nod, half-shake. It meant, and she understood: She’s apples, things are good-oh.

He’d asked her to marry him. Better to marry than to burn, said the saint. But this pair weren’t dying from unconsummated love. She didn’t quite know why she was getting married, since she didn’t ‘have to’, like one of her sisters. They’d known each other for three years and it was a time of long engagements. So they didn’t have to rush into anything. He was both straightforward and enigmatic, her Ben; she supposed he had become her Ben. One day she saw him taking pills.

‘What are they for?’ she asked.

‘Headache,’ he said. But they didn’t look to her like harmless little Aspro tablets. He seemed healthy enough, but given to furious bouts when crossed. And he was irrational. At times, when he stayed the night, or stayed until the early hours, he woke her up to whisper, ‘Willa, I think I’m going to die.’

‘We’re all going to die,’ she replied sleepily.

‘No, no, I mean tonight. My heart’s beating, feel.’

‘Of course it is,’ she said, feeling his chest. ‘Ben, you’re not going to die tonight. Now, are you going to sleep, or are you going home?’

He never made any allusion afterwards to these exchanges, these dark nights of the soul when he was like a mendicant and she the oracle. It was as if his fear and her cursory reassurances had never taken place.

‘You shouldn’t drink so much,’ she said once, but mildly, as if she had no stake in the matter.

‘I don’t drink much,’ he said, showing surprise.

This made her shrug. Everyone drank too much.

She’d been saving her money to go to Melbourne, the heart of the rag trade. They had fashion houses there where design was taught. But Ben had gone down on his knees for her, right beside her sewing machine.

‘I’ll do anything if you marry me,’ he said. ‘I’ll give up the drink.’

When he looked at her in a certain way, when she saw his head bent as he flicked open a cigarette paper and rolled a makings, holding an audience in thrall to one of his stories, she knew that in this life there was only to be the one fatal mate.

‘It’s not exactly that I want to change you,’ she said, slowly. ‘I don’t want some kind of convert on my hands. But,’ she thought to add, ‘cutting down wouldn’t hurt.’

‘But he’s a Catholic,’ said Eve.

Willa raised a shoulder.

They were seated in Willa’s bed-sitter on either side of the sewing machine. She had folded its neck and hand-wheel down into its own depths so that it could do service as a table. Its black top glistened and Willa placed a small hand-embroidered cloth over it, before placing the tea things on top.

The two women sipped, then the younger cut dainty slices of home-made cake. An electric heater on the floor glowed pink. Willa wore a woollen skirt and a jumper with diagonal broad stripes, stockings and shoes, little make-up. Her sister wore a grey silk dress with a cerise belted overcoat, and a little hat perched jauntily on her head, only half hiding well-coiffed hair. She had underscored all this with a single string of pearls.

It was said, indeed whispered maliciously by some, that it was strange how the sisters always managed to dress so well on a tailor’s wage. But their clothes, hats, even, were products of their own hands, hats made with buckram shapes and a remnant of velvet with a small length of coarse ribbon. They pored over pattern books for ideas on dresses.

‘Lovely cake, Sis,’ said Eve, dabbing at her lips and lighting a cigarette.

‘Gina made it,’ said Willa. ‘Lisa delivers it!’

‘Good people,’ said Eve, nodding, giving the seal of approval Willa didn’t need.

They sat a while, companionably enough.

‘As I was saying, he’s a Catholic.’

‘So is Gina,’ Willa said.

‘You’re not going to marry Gina,’ snapped Eve.

‘I don’t have to turn. It’s not as if we’re going religious.’

‘Mm.’ Eve subsided. ‘What do you have to do, then?’

Willa was looking at her sister and smiling. How she changes, my Eve, she thought.

‘I have to bring up any children in his faith.’

Eve drummed now empty fingers.

‘Has he got any faith?’

‘Not too much,’ Willa said with something like a grin. ‘I want to change the subject from Ben. Not all men can be perfect. How’s Jock?’

‘Jock’s far from perfect for me,’ Eve said.

Willa leaned over and covered the other’s hand as though to still it. ‘It’s all right, Eve, it’ll work out, Sis.’ As if she were the elder.

‘I promised them, you know very well, that I’d look after you.’

‘But I’m not a youngster! It’s not as though I’m still sixteen.’

She put away the used crockery and they prepared to go downstairs together, to do some window-shopping.

Her other sisters had given up. Willa was in danger of being over the hill, long in the tooth at twenty-five. So she might as well please herself and marry the man.

My friend and I, my best friend and lover, decided one night to call it a day. And no one will ever make me laugh so much, I thought, or weep so bitterly. Ha-ha, boo-hoo. No more madness for me. I’d be on my own but without the loneliness.

Yet it has happened again. With time running out, I am utterly, foolishly, in love. Work is carried out as though normality prevails but head and hormones are in an uproar, just when I thought they were sleeping.

Incapable of a mere crush leading to, perhaps, a fling, it has to be, apparently, this obsessive preoccupation. And with it the inexhaustible bombardment of a lover’s questions: what would the other’s face be like, breathing close, on a pillow? Her dear freckles close up. How would those hands touch and define me? Had there been boyfriends? Girlfriends? I do not stoop to star signs. Does she like good food and drink? Who does she dine with, confide in, walk with? What makes her laugh and whom does she admire?

Indeed there are so many gaps in my knowledge I wonder what the basis of the attraction is. Except that you don’t need a lot of information to know that lodestone of ardent wishfulness.

Mary�

��plain as any name can be—the unwitting cause of this passion, is involved with life. She is the chief life-giver and facilitator, to use the modern word, for humanity’s spent life-force. To put it clearly, she is a geriatrician; not merely involved in keeping them alive but in making life worth the effort.

Myself, I am more preoccupied with death. Perhaps a better way of expressing it would be to say I am interested in the progression of decay and the beckoning of the grim reaper, that spoilsport.

There have always been octogenarians. At twenty-six I had three good friends who were all over eighty. Their attraction for me was never simply in their old age but in the fact of their downplayed humour and all that knowledge at their fingertips: the slight laugh old ladies emitted when youth uttered a worn-out statement, thinking it had just created a new notion.

That immediate grasp the olds have on favourite topics. Yes, said my former French teacher, Thurber was more important than he’s ever been given credit for. No, said my aunt, consciousness of our own mortality was not the way she would define humankind’s distinction. And William the geographer asked gravely: Did you see Venus last night—in the east, at about 3.00 am? He put it with the same acuity and sense of romance he probably had at age thirty.

My friend Ruth, science graduate circa 1932, seems amused by her own age. ‘The trouble with having read physics so early in the century,’ she said recently, ‘is that the atom hadn’t yet been split!’ She thinks this mistiming of hers is uproarious, in retrospect. But what captivates Ruth—lover of art works—about the phenomena of Art and Science is that she believes them to be riding in tandem through history. She sees the energy of the Renaissance as an echo of Copernicus; she is persuaded that Picasso and Ibsen owe their notions of relativity to Einstein.

The Seamstress

The Seamstress Trio

Trio